Inside Sector Key West

USCG Sector Key West

On a 70 degree, blue sky, December day in Key West, I found myself on the west end of the island, outside the guarded, metal gates of the United States Coast Guard Group, Sector Key West. A young, round male in wrinkled blues, held the gate house secure against the food delivery guy and me.

On the nose of 1 PM, my escort arrived. Lt. j.g. Peter Bermont, the USCG’s spokesperson in Key West, and my affable government handler for this interview. He provided me with a tour of the Station and the Cutters, while keeping me out of the secured areas I most wanted to see with a smile and joke. We briefly discussed the mission and activities of the USCG in the Key West Sector, while meandering about the base, getting a view of the ships and buildings. A majority of their focus appears to be on life saving activities, either of Cuban refugees on makeshift rafts, or Search and Rescue in local waters. Enforcement of environmental laws regarding fishing and polluting being the next most significant consumer of time and effort.

Commander Reed

After the tour, I had the opportunity to interview Commander John W. Reed, USCG, Deputy Sector

Commander, Key West Sector. Greeted by a warm grin and handshake, the Commander invited me in to his classic office space to talk. Fluorescent lights bathe the room in the surreal, sterile glow of electrified gas reflected off foam ceiling tiles, sheetrock and wall to wall carpeting, generating the “work environment” atmosphere that only fluorescent can. Combined with the deep brown wood stained and leather furniture, I have to pause for déjà vu , as I was transported to my father’s office decades ago. Along the wall and on the shelves here, instead of business awards, hang career service honors.

Commander Reed has been decorated 4 times for his service. Once while serving in the White House and once while serving in Haiti as US liaison to the international efforts there. Twice while serving here in Key West. The Commander has had an interesting career that almost wasn’t. His first application to the USCG, encouraged by referee at his high school football games, was turned down. He went on to college, on a football scholarship, and was then called the following year to re-apply. This time successfully entering and graduating from the academy in 1993. Only to find himself patrolling Alaska, during the winter, from the Seattle base; a dramatic change for a kid who grew up in Los Angeles.

Haiti

After serving as liaison between the USCG, the White House and the Caribbean Drug Interdiction Task Force, he moved on to Southern Command where he served as liaison between the US and the 26 nations involved in the 2010 disaster relief efforts there as part of UN OCHA.

His descriptions of the efforts in Haiti are less than encouraging. This was just after the earthquake and hurricane, when a cholera epidemic was spreading across the island, far faster than doctors had expected. To this day, Cholera remains epidemic, with the first signs of good news arriving this past summer as mortality rates began to decrease and vaccinations hit their second target level.

The UN was spending roughly $900 million annually in Haiti, a project the Commander referred to as a new “Humanitarian Industrial Complex.” The goal was to provide them with the infrastructure and systems to deal with their issues themselves. This involves training, resource allocation and the building of Community Clusters; a center containing a school, a medical clinic, a community center, and warehousing facilities. The resulting influx of personnel and materials into a region previously lacking education and/or infrastructure generates significant opportunities for profit as long as it continues.

I asked him about progress of the UN project during his time in Haiti, he grimaced, said it was generally positive but “…you don’t see the widespread change you would hope for.” He had praise for the capabilities of the Haitians assuming leadership roles, but the lack of infrastructure or mass education constrains their ability “to achieve their ambitions.” Describing the scenario, related to hygiene and infrastructure as, “…not even what you would expect to see in small town America.”

Drug War

Experience has taught Reed a similar, pragmatic view of the drug war efforts vs results. Though this is not a significant task for the Key West sector, except when interacting with other agencies or governments, he does have a great deal of experience via the White House Inter-agency Task Force. The Coast Guard, as an agency that is involved in both military and law enforcement operations, has a unique position that makes them particularly well suited for these task forces.

Under the DOD via JIATF (Joint Inter-agency Task Force) South, the USCG is involved in Interdiction; tracking and stopping suspected smugglers with the assistance of aircraft, satellites and ships from other agencies and nations. Then Apprehension begins, civilian command in Miami takes over and gives orders to board, detain, etc. This is more than a technical change, the military is legally prevented from police duties, therefore putting responsibility for the operation in civilian hands is an important legality. While the Coast Guard is executing the commands either way, authority and scope lay with entirely different agencies of the government. Whether that organizational theory means anything to the smuggler caught with kilos of illegal product, I couldn’t say for sure. But the Coast Guard officers and crew have to be prepared for both civilian and military missions, a burden few agencies carry.

Though quite animated about the structure and implementation of the Coast Guard’s drug war efforts and their ability to execute, Commander Reed’s discussion on policy was more subdued. The goal of the Interdiction Committee he served on was to remove enough product from the black market to “drive up the price and reduce the purity of the product on the street.” They figured 20% would be effective, a goal they were making. However the results were not as expected, “there was not a lot of change in price, not a lot of change in purity. “

A fact which appears to have had little effect on policy. In 2013, the USCG claims credit for interdicting $3 billion of illegal drugs, in just over 80,000 hours of work. That is 5000 fewer hours than 2012, but still 7000 more than 2011. Meanwhile the White House commissioned report on drug use in America, 2014, shows that illicit drug spending overall is fairly stable, though it changes between products, and overall quality is improving. Which would suggest that the cartels are immune to the efforts of the drug war.

He summed up his experience with the drug war, “You have to find a balance. What are your goals? You don’t want this stuff on the street, but you know there is a limit.”

Cuba

By far the largest segment of the Key West Sector’s resources and time are dedicated to rescuing and repatriating refugees from Cuba. Commander Reed estimated it at 70% of total workload. The priorities, as given to the Sector from the Admiral, regarding Cuban immigrants (paraphrased for space):

1) Save Lives

2) Deter future “boat lifts”

3) Stop and arrest human smuggling for hire

4)Stopping the immigration by raft movement

The saving lives priority was reiterated throughout the day when discussing the Cuban immigrants. SOLAS, The Safety of Lives at Sea convention, being a top priority for the Coast Guard. This was far and away the most intense focus of the discussion. The description of the rafts, of the condition of the people, of the nature of the trip, all revolved around the danger to life and limb.

He described for me a scenario leaving one to wonder how desperate you would have to be to attempt such a thing. 90 miles at 1-5 knots will take several days. Several days, often on a homemade raft, with little water or food, no toilet, no protection from the elements, and crowded for space with as many desperate refugees as could fit. Several nights with the ocean winds tearing into your flesh. Followed by hours of sunlight baking the sea salt into your skin, and everyone on board, including you, beginning to stink. And just as you get in sight of land, if you can just live another day, a Coast Guard cutter comes along, scoops you up, saves your life and sends you back to Cuba.

Though aircraft patrolling the region are the most common method of detecting the rafts, often passing cruise ships or fishing vessels will randomly encounter groups crossing the 90 mile strait. During the summer, the Coast Guard will make 3 or 4 trips a week repatriating Cuban immigrants collected from the ocean.

From pickup to return is a process usually taking about 5 days. The refugees are held aboard a Cutter, attended by a mid-level medical provider, and biometrics are taken for screening. If there is documentation of them living in the US before (criminal or legal), they cannot be returned Cuba. So they are sent to a special section of Guantanamo Bay (not the terrorist section) to await a 3rd party nation to accept them. If they have no medical or legal issues, and they cannot demonstrate a credible fear of harm/retribution if returned, then the Cutter docks in Cuba and everyone goes home. The process has become so routine that anecdotes exist of Cubans taking 2 week vacations to make the attempt, knowing if they fail, they will be returned in time to go back to work.

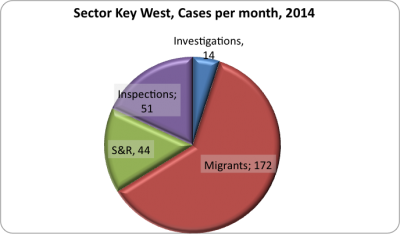

Source: USCG, Sector Key West

A Cutter mission is billed to the government at an average fee of $9,519/hr. This is before any food or medicine costs for the migrants, non-USCG costs to other agencies, and miscellaneous expenditures not accounted. At 5 days, a single interdiction and repatriation could run, approximately, $1.2 million; depending on type of craft and other variables. During the summer, they can run 3 or 4 repatriation trips to Cuba in a week. All of this to support US policy of embargo and Cuban policy of letting no one leave, resulting in a dangerous and expensive situation that fails to achieve either nation’s goal.

When discussing Cuba with the Coast Guard officers, there is no mention of the policy. The conversation immediately jumps to their life saving mission priorities followed by the ships and equipment they get to play with. Leaning in and gesturing with upturned palms, both men I met this day were sincerely enthusiastic about the mission of saving lives. When describing the condition of the refugees, not just the rickety vessels they float across the straits on but also their frail condition after a few days at sea, the empathy in their tone is tangible.

Search and Rescue

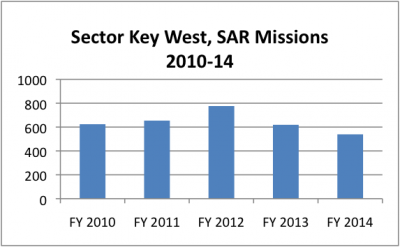

The USCG has numerous missions. They investigate commercial pollution and overfishing. They inspect boats, maintain navigation networks, and support other agencies. In Sector Key West, after the Cuban migrant interdictions, Search and Rescue operations are the next most significant mission.

The Coast Guard uses the following metric to determine their success:

= ________LS__________

(LS + (LLB + LLA + LUF))

Where:

LS = “lives saved”

LLB = “lives lost before notification”

LLA = “lives lost after notification” and

LUF = “lives unaccounted for” (or missing) as defined and input into MISLE.

Source: USCG.mil

For the last 6 years, nationally, they have been better than 75%, 80% when adjusting for lives lost before they were contacted. Though I did not have numbers for lives saved or lost in the sector specifically, if the trend holds true that would be at least 430 lives saved in Key West during 2014. Discussing this aspect of their mission with the Commander brings up anecdotes of humorous misadventures at sea by the unprepared or intoxicated. After a few moments, Reed’s face turns like pages from one emotion to the next, growing serious, he recalls scenarios that ended tragically. This quickly rolls into the theme of preparedness. The frustration of loosing people to unforced errors, preventable with a proper comm., flare, anchor, etc. clearly shows as he recounts recent events where they were too late.

Recently, two men, in-laws, were diving and came up to find their boat gone. One pursued a boat light nearby and the other was taken by the current. The first managed to cling to a buoy and get rescued after several exhausting hours, but the second remains lost at sea to this day. The USCG recently announcing they had to give up the search due to time and temperature of the water. Reed described this situation as all too common, where people believe their anchor is secure because it is hooked and taught, when in fact it needs to be slack with anchor and chain lying across the ocean floor. As a result, the ocean current pulls at the already taught chain and tears it away, casting the boat adrift. There was no humor or mocking in this recounting, as he was all too familiar with the real world consequences of the simplest oversight at sea.

The Future

The US Coast Guard, as an officially named organization, will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2015, though it has been around in one form or another since 1790. Sector Key West has been an official entity since 2004, though there has been a government customs presence here since 1824. As the fleet becomes updated with faster, more versatile Cutters, drug laws around the nation change, relations with Cuba are in flux, and waterproof communication technology improves; one has to wonder what future operations will look like for this US Coast Guard.