FIGHTING FIRE IN KEY WEST

by Dennis Reeves Cooper…….

Today, if you dial 911 to report a fire, the Key West Fire Department will typically be at the scene of the fire within five minutes. When I was researching this story and former Fire Chief Eddie Castro gave me that information, I asked the question again. “Come on, Chief, five minutes from the time the call comes into the fire station to fighting the fire does not seem credible.” “Well, actually,” he said– lecturing me like one of my old professors– “the response time is more like three minutes. With three fire stations on the island, we are close to most potential fire sites. And when a call comes into one or more of those stations, we can usually be out the door within a minute and, then, at the fire scene within a couple more minutes.” This gives a whole new meaning to the term ever-ready. And combine response time with state-of-the-art “apparatus”– the millions of dollars worth of fire engines and other equipment– as well as 88 highly-trained firefighters– and you have a situation where most fires in Key West don’t have much of a chance to cause catastrophic damage. But it wasn’t always this way.

Key West’s first volunteer fire company was organized in October of 1834, six years after the incorporation of the city. But less than three months later, when the little company failed to respond to a small fire, Stephen Mallory (Mallory Square is named after him) called for a meeting to form a more efficient fire company. Twenty-five men volunteered and a hand pumper was purchased with donations from the public. The way it was supposed to work was that, if there were a fire, 8-10 firemen pulled the pumper to the site of the fire. Another group of firemen pulled a hose reel to the site, where the hose was connected to the pumper. A bucket brigade filled the pumper with water and 6-10 firemen used the long handles on the pumper to pump water through the hose. Who manned the bucket brigade? All or most residents kept a bucket on their front porch (or somewhere else handy) just for fire-fighting purposes, and the bucket brigade was manned by both citizens and firefighters. The water came from wells, cisterns where residents stored rain water, or from the ocean, if the fire was close enough to the waterfront. There was no municipal water system at that time.[wds id=”51″]

The new pumper was rarely used, except for parades. And, as it turned out, that was fortunate– sort of– because, when a fire broke out in a large wooden warehouse in 1843, fire fighters learned that the engine was unfit for use– and the warehouse burned to the ground. In typical Key West fashion, citizens carried the pumper to the end of the Simonton Street wharf and threw it into the sea.

As late as 1859, there was still no organized body of firemen in Key West. So when the city’s first large fire broke out in a warehouse at the corner of Front and Duval Streets, the fire blazed out of control for eight hours. Although the military firemen fought the fire with whatever equipment they had, all but two buildings in a two-block area were destroyed. It is possible that the entire city could have been destroyed had it not been for a citizen by the name of Henry Mulrennon. He was able to procure a keg of gunpowder from Fort Zachary Taylor and blow up a house next door to his own residence at the corner of Fitzpatrick and Greene Streets– which prevented the fire from spreading. While it is likely that most of the residents of the city appreciated Mulrennon’s quick action, history does not reveal what his neighbor thought about it.

The fire company here was reorganized again in 1875, consisting only of Hook & Ladder Company No. 1. The only fire-fighting “apparatus” available to the new company was a hand pumper borrowed from the Navy and a four-wheel hose reel. Soon, however, the City purchased a state-of-the-art Button steam engine. The term state-of-the art here means that the fire engine would now be pulled by two horses, rather than a group of firemen. Also, an on-board coal fire would be used to turn water into steam to generate pressure to push water through the hoses– rather than requiring firemen to pump water by hand. As far as the firefighters were concerned, the modern world had arrived. Keep in mind that this was before motorized vehicles were in general use.

Then as now, the fire department participated in all parades. That was the case on July 4, 1876. The parade was led by the shiny new Button steam engine and the City’s 75 firemen, marching in their new uniforms. The parade headed toward the new City Hall on Greene and Anne Streets (what we call Old City Hall today) and the new fire house right behind City Hall. Flags were flying and music was playing– and no one noticed that a cannon discharge had caused a fire on the roof of a nearby house. When the fire alarm sounded, however, all 75 firemen responded to the fire with their new steam engine– and put the fire out within 10 minutes.

There was a different outcome on March 30, 1886, when what would be Key West’s biggest fire to date broke out next door to San Carlos Hall on Duval at Fleming Streets. This was a popular meeting place for Cuban revolutionaries. Unfortunately, the Button steam engine had been shipped to New York for repairs– and although the firefighters responded promptly, they only had the hand-pumpers to fight the fire. The fire quickly spread to surrounding buildings and blazed for 12 hours, destroying two-thirds of the City’s business district– including City Hall and the fire house behind City Hall. City Hall and the fire house were rebuilt and a second fire house was built behind the county jail on Fleming Street, between Whitehead and Thomas. The following year, 1887, another fire house was built on Division Street (now Truman Avenue), on the convent grounds near Simonton Street.

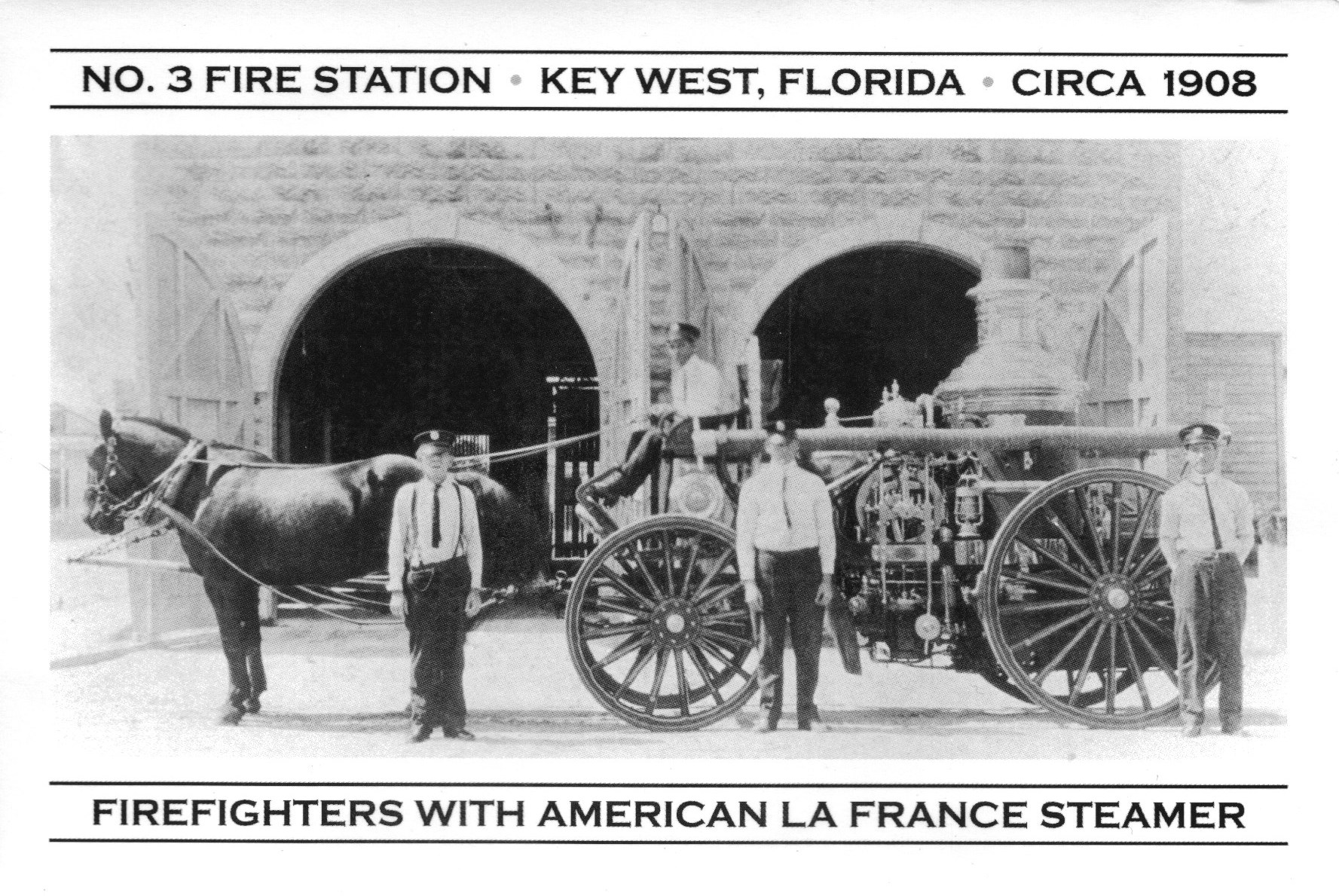

As the fire department grew in size, so did the number of horses required to pull the steamers. Eventually, the fire department here would own more than two dozen horses, with four horses assigned to each of the three fire houses. Stalls for the horses were maintained at each of the fire houses, and firefighters were assigned to care for the horses. When there was a fire call, the horses were led to the front of the fire house where they were hitched to the steam engines. Reportedly, some of the horses were smart enough to react to the fire bell by walking up to the front of the fire house on their own and positioning themselves in front of the engines. The horses not on duty were kept at Fire House No. 1 behind City Hall or in a corral on Grinnell at United Streets.

Improvements continued over the years. In 1888, a water-works system for fire fighting purposes was constructed city-wide. The system used sea water. That same year, Western Union constructed a city-wide fire alarm system. That system would be upgraded in 1906. The use of large fire alarm bells were also used. One bell was placed on a tower on the school grounds at the corner of Division and White Streets (now the Harvey Government Center). The tower and bell was later moved to the cemetery. Another bell was located at City Hall. A new Fire House No. 3 was completed in 1907 on the corner of Grinnell and Virginia, replacing the fire house on the convent grounds. Putting the new fire house into service was delayed for several months, however, because– you guessed it– there was a fire at the fire house. This historic building is now the Key West Fire House Museum, which preserves the 182-year history of the Key West Fire Department.

By 1917, the Key West Fire Department was completely motorized, bringing the era of the horse-drawn steamers to an end here– almost. Apparently, at least at first, fire officials here were not completely sure about the new-fangled motorized fire trucks. One steamer was left in reserve at Fire House No. 3– which meant that at least some of the horses didn’t immediately lose their jobs. The fact that the KWFD was motorized by such an early date is impressive– since the first motorized fire engine was not even manufactured until 1905 and there was no fire department in the United States completely motorized until 1906. One of the displays at the Fire House Museum is a shiny red 1929 fire engine. This truck was never used in service here, but rather was purchased as an antique by local businessman Ed Swift in the mid-1990s, restored and donated to the City of Key West.

Over the years, there have been many improvements and innovations at the Key West Fire Department including, of course, the state-of-the-art equipment making firefighting more efficient here. New to the department within the last year is providing emergency medical and ambulance services. These services were previously provided by private contractors. The Fire Department’s Rescue service responds to calls concerning traffic crashes, heart attacks, falls, drownings– anything where emergency medical or ambulance service is needed. Three rescue units are in operation, each manned by an emergency medical technician (EMT) and a medic. In critical situations, additional personnel can be brought in from other department units. All fire fighters are also EMTs.

Innovations in training have also been introduced. For example, some juniors and seniors at Key West High School are spending part of each school day at the Fire Department, learning what it takes to be a firefighter. Following graduation, if they complete this two-year junior fire academy and they choose to pursue a career as a firefighter, they will already be half-way through the required training. “This gives the students the opportunity to experience fire training in a realistic environment,” said retiring Fire Chief David Fraga, “and it’s good for the department because it gives us a leg up on recruiting and retaining good firefighters.”

~~~~~~~~

ENDNOTE: Much credit for the information included in this story must go to retired Fire Captain Alex Vega, He is, for all practical purposes, the official historian for the KWFD. And the Fire House Museum was his brainchild. “In 1998, the historic Fire House No. 3 was replaced by the new fire house on North Roosevelt Boulevard near Jose Marti Drive,” Vega said, “and there was talk that the building might be sold to a condo developer or, even worse, torn down. So I and other active community volunteers as well as active and retired firefighters formed the non-profit Old Firehouse Preservation Inc, and we were able to eventually lease the building from the city. It took 15 years to restore the building and turn it into a museum– and we celebrated our grand opening in January 2013,” he said. The Museum is located on Virginia at Grinnell Streets and is open 10am- 3pm, Tuesday-Saturday. Admission is $10– but half-off for locals, firefighters, police and military. No charge for children under 12.