Q&A with Tito Davis, Author of Gringo: My Life on the Edge as an International Fugitive

What if tomorrow, you had to leave your family, your home, and everything you’ve ever known to become a fugitive in a country where you couldn’t even speak the language?

Do you think you’d survive?

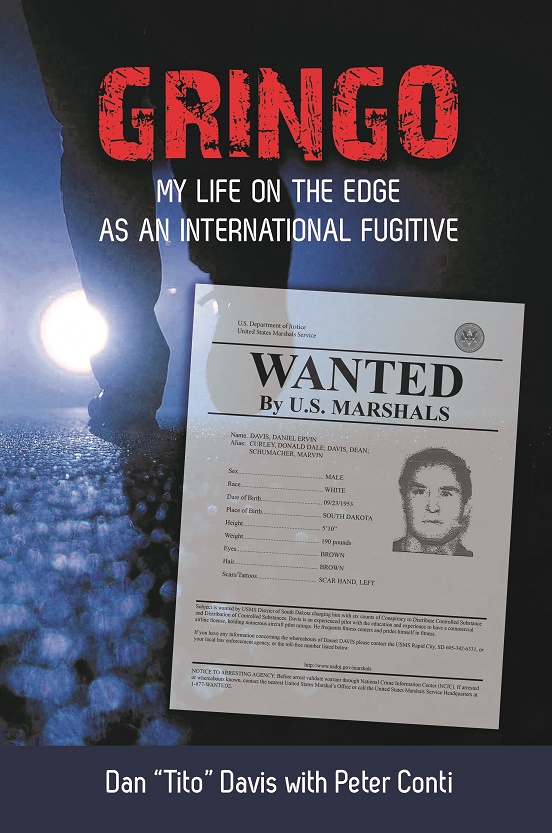

Dan “Tito” Davis did. In his real-life memoir, Gringo: My Life on the Edge as an International Fugitive, written while serving a 10-year prison sentence, he details his shocking story of the 13 years he spent on the run from the United States federal government.

Davis was released in 2015 and now lives in Key West, Florida where he is part of the local writer’s guild and enjoys fishing, playing pickleball and bicycling around town. Media Connect, a division of Finn Partners, caught up with Davis to ask him about his time in Key West and his time spent on the run.

Pick up a copy of Gringo on Amazon or at GringoBook.com!

Media Connect: How long have you been in Key West? What drew you here?

Tito Davis: I’ve been living in Key west for a year and a half. I love it here.

When I was kidnapped out of Venezuela I’d been living in the tropics for many years. I wanted to be in a warm tropical environment with an artistic community. I was working on a book about my life as an international fugitive and wanted to be around fellow writers to learn from, but I didn’t want to live in a major city. There probably isn’t a better place in the entire United States than Key West that can provide the warm, tropical, artistic town criteria.

MC: What have you found most challenging about adjusting to life in Key West?

TD: The technology war is my biggest problem but the people in Key West have been very helpful and kind to me.

When I arrived in Key West I had not been on the streets of America for 22 years! I had missed a generation. I had just been released from the Bureau of Prisons and was now in another world. It was total shock- like coming out of a time warp. When I left the country gas stations still had attendants and people still used fax machines. People rarely used the internet as there were no smart phones. People still used maps. No one knew what GPS was. When I went to buy a phone, the person assisting me asked me if I had been living in a cave. I hold him no- federal prison. I was lost I had no idea of where to start. I didn’t know what a text message was or how to send one. That gentleman at the phone store became extremely helpful. I found my way to the store almost every day with questions. People were ordering pizzas with their phones, taking pictures, texting, using Facebook. It was difficult to comprehend.

MC: What is it like to be on the run? In the book, you have a casual, collected voice most of the time—how often were you worried and paranoid about the situation?

TD: Being on the run is not like it is on a TV show. Everything is stacked against you; if you do a million things correctly and one thing wrong, you could go down. It took years of homework before I was somewhat comfortable, but I was always looking, thinking, or feeling danger.

I spent hundreds of hours, if not more, reading and studying how fugitives were caught; most (over 90% per my resources) were caught via traffic stops or someone reporting them to the authorities. Those were domestic (USA) numbers. I figured that if I left the country, my chances of remaining free would be better. If I didn’t contact people I knew from my prior life, never did anything illegal or broke any local laws so that I would never be arrested or finger printed, and never returned to the USA, my chances of having a new life would be improved substantially.

This wasn’t a vacation but a job. I researched opportunities while attending a number of universities under aliases, not to obtain a degree in these foreign institutions, but to acquire the knowledge to be successful in a land of strange languages, different customs, and serious challenges.

MC: Much of your time in the book is spent on the run in different Spanish speaking countries. What’s it like having to adjust to an area where you can’t even speak the language?

TD: When I left the United States for Mexico, my Spanish was horrible. I didn’t even know how to ask for the bathroom. Not knowing the language is a major barrier regardless where you are, but when you are a fugitive trying to start a new life and need paperwork, it’s an added risk to need someone else to translate your words to the right people. It’s hard enough when you must accomplish something illegal in a place where you know the language and the customs. When your back is against the wall.

MC: You originally got in trouble with the law for selling a narcotic that was legal at the time, and now that marijuana is becoming legal (the second drug you sold), how do you feel about the criminalization of drugs in the U.S.? Is it strange that now, if you lived in Colorado, you could be an everyday businessman with medical marijuana?

TD: In my opinion, they should legalize and tax drugs in the USA. If the government is spending billions of dollars fighting a war they can’t win, it’s time to rethink their position. With the money they save through legalization, plus the additional money the government would make through taxes on legalized drugs, they would have the funds to spend in education, transportation, healthcare, and other programs without raising taxes and maybe even lowering them. It’s a practical solution to a lot of problems.

As for how I feel about how what I did would’ve been legal, everything in life is timing, venue, and location. Hugh Hefner of Playboy fame was trying to get pot legalized over 50 years ago, and finally the ball is rolling. There are many people moving to those states to take advantage of the legalization of recreation marijuana, be it for health, medical, or business reasons. For example, several former DEA agents and other former law enforcement officials have moved to Colorado and gone into the legal pot business. In my opinion you can’t blame them for switching sides. It is only a matter of time before other states are going to legalize marijuana and acquire a new source of tax revenue.

MC: In your book you make many references about how hard it was to go straight after a stint in prison even though you wanted to. Can you elaborate on this? What’s the biggest obstacle, and what do you think could be done to help recidivism in this country?

TD: When you get out of prison, you are a convicted felon. Most people have no idea what that means, but basically you are a second-class citizen. You can’t vote, you can’t hunt with a gun or be around firearms. There are several licenses that you can’t get depending on the state: a real estate sales license, for example. The laws, rules and regulations pertaining to felons make it extremely difficult to get many jobs.

In addition, many felons have no real job skills and had no vocational or other training while serving their sentences to prepare them for life on the outside upon their release. Many have fines, restitution, child support, owed taxes or alimony payments, and have no health insurance. Without a support group and/or the help of your family and friends, things are incredibly difficult for someone released from prison.

In my case, I wanted to fly; I had an airline transport license. The Federal Aviation Administration had no problem with me flying commercially, but my parole officer said that she couldn’t supervise me so she denied me getting a flying job. I appealed her decision but it was upheld. Next I decided to go to school to obtain a real estate sales license in Las Vegas, Nevada. I was told that felons couldn’t get a real estate license in Nevada. So, my first two ideas of a job that I would have liked and I could have made a decent living on were struck down. I finally got a job telemarketing and another one working for an accountant, basically delivering papers and playing gopher.

I knew that with these two jobs I would never be able to do more than survive. I also had an IRS tax lien against me. I was unhappy that my ideal employment was impossible. Not seeing much opportunity for advancement, I decided to get back into the marijuana game.

To combat recidivism, the biggest asset would be full training programs for prisoners so that once they are released, they would have a serious chance of acquiring a decent paying job and becoming a tax-paying resource to society rather than a burden.

MC: You’ve rubbed shoulders with some of the richest members of society, and some of the poorest. Did that teach you anything about the systems that govern us, or people in general?

TD: From what I’ve experienced, when you’re in a jam, the poor people are the ones that are going to help you- probably because they’re used to facing their own difficulties. I remember one Christmas I was walking through a pueblo in Mexico feeling sorry for myself. I was trying to figure out where the house I was staying in was located. I saw a family of campesinos, farm workers, in the street, preparing their Christmas dinner. They had a beat-up piece of tin which came off one of the houses, and they were using it like a grill to cook. They were heating up some tortillas and some butcher’s meat. Their kids were playing with Christmas toys in the dust. In an incredible gesture, the father saw me and invited me to join them for Christmas dinner. It was overwhelming. People who have nothing in Latin America will usually help you out.

The rich people on the other hand seem to analyze you and judge you, and they’re asking themselves “what’s in it for me?” If you can’t help them, be an asset to them, or help them achieve a goal, they’re probably not going to help you.

I remember another story of a friend of mine who was in jail and he needed socks and underwear. Somebody called up a sister at a church and asked if she could give him some clothes. The sister replied, “What if some people from my church see me coming and going from the jail?”

What can I say? Everyone has a different outlook on what is right.

MC: What’s it like having to run from your family? Or to know overnight that you’re almost never going to see them again?

TD: When I knew that I had to leave the United States or spend the rest of my life in prison, the decision was made for me. I remember my mother telling me “be brave.” Those were the last words I heard from my family until I was kidnapped in Venezuela.

I was hoping that I could do a minimum amount of time, go on with my life and keep my relationship together with my wife, but I knew that was a dream. The three prosecutors who had my case said that they were going to make a career with my conviction. Once I knew that, I paid my bail, and decided I had no option but to flee the country.

MC: What was the scariest situation you found yourself in as a fugitive?

TD: When I arrived in Columbia one year after Pablo Escobar was killed, it was totally different than any place in Latin America I had been to. The government oversaw zones in major cities like Bogotá and Medellin, but outside of the cities the guerrillas controlled the country. In Columbia at that time, two men could not ride a motorcycle together because motorcycle assassinations were so common (the guy in the back would be a shooter, and the driver would zig through traffic, let the shooter empty a clip into a car, and drive off). Motorcycle riders were forbidden from wearing helmets so they could be more easily identified.

If a young child went out as a sicario, an assassin, to kill someone, his mother would not feed him beforehand. Why? Because the mom knew if her child was shot and started losing blood, the hospital would have to pump his stomach before surgery, which meant more time lost and a higher chance her child would die.

However, the scariest situation was when they had me on the hot roof of a Venezuelan jail sitting on a metal chair underneath the tropical sun, handcuffs behind my back, being interrogated. They started telling me that they knew my passport was a fake, and listed off the details of who I was. I knew things were going to get very serious, and I had probably at most 72 hours to get out of that jail or I would go back to the US to do a life sentence.

What saved me was that the colonel ordered his lieutenant to go to the British Embassy to see if I was wanted. The lieutenant left with my Venezuelan cedula, and because it was not registered in their system I came up clean. If he’d have gone with my passport, it would’ve been game over.

MC: If there is anywhere you could go again, where would it be?

TD: Venezuela is my home outside of the United States. I love the people and the culture. But in general, I love Latin America. Each country is unique. I intend on returning and living in Latin America at some point. They’re great people who were always good to me.

MC: Can you compare Key West to any of the places you lived during your travels?

TD: I literally went around the planet looking for the best country to start a new life. I studied under aliases in various universities in foreign countries looking for opportunities, researching businesses and customs (54 countries, 5 continents). I had never been in a place like Key West, though. Here you feel isolated but you know you aren’t. There are a few equally beautiful places around the world, but none with the infrastructure and charm of Key West. Key West has restaurants, bars, music, nightlife, weather, beaches, sun, watersports, and tours. The local county parks and beaches are very well maintained! Things work here. There isn’t smog, serious crime or filthy streets with no man hole covers for you to fall or drive into unlike many other parts of the world. You are safe walking the streets and riding your bike at all hours. The island is bike friendly which I truly enjoy.

In many of the Latin cities you don’t stop at a red light because of the threat of being carjacked. When the sun goes down steel shutters drop in front of the businesses windows. In Venezuela you go home and stay there until the sun comes out.

You can’t compare anther small town in the world to Key West. It’s a special place.

MC: Is there a message you want people to take away from your book?

TD: My message to the people would be never, never, never give up; always go forward! In the gloomiest, darkest, and ugliest of times, try and find something positive. If you’re alive, you can find something positive to cling to and keep moving forward.

Tito, would love to have you come by for Happy Hour. Email us via Naja.